Messaging Matters

What Makes a Strong Message?

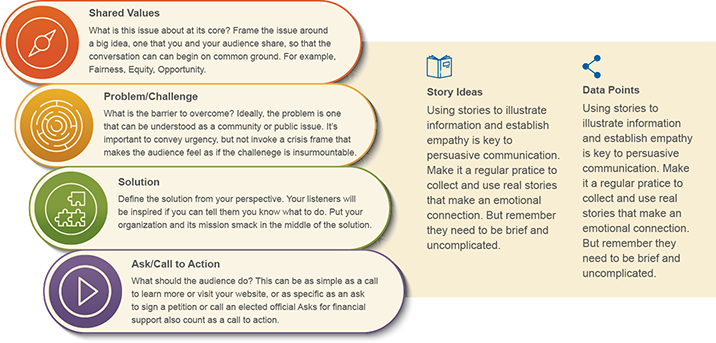

Message Tower

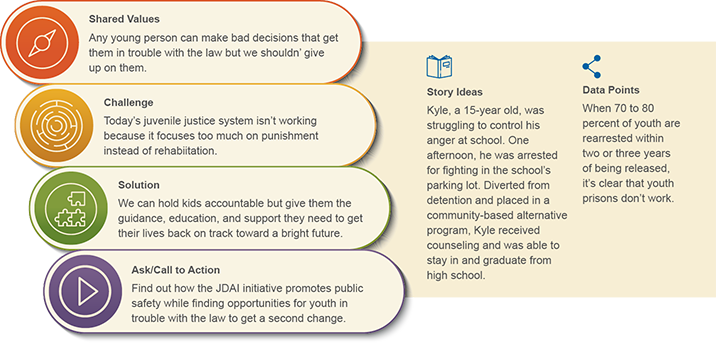

Juvenile Justice Message Tower: Example

Messages are short, clear statements that convey information and emotion, opening the right door to understanding.

Messaging Do’s and Don’ts

- Advance

- Short, concise descriptions

- Relatable language

- Positive, inspirational tone

- Demonstration of impact and outcome

- Clear, simple call to action

- Avoid

- Messages which try to capture everything

- Messages full of Jargon

- Messages which only focus on process

- Messages that ask too much

Research-Driven Message Development

In 2015, the Casey Foundation enlisted the support of expert communications and public opinion research agencies Fenton and Global Strategy Group to collect objective information on how voters understand the juvenile justice system. Throughout this toolkit, you can see lessons learned from our research. To begin, we gleaned critical takeaways about what the public currently understands, or even misunderstands, about the juvenile justice system and which messages, arguments and data points are most likely to shift public support toward reform.

In order to be effective messengers for reform, it is critical to first understand your audiences. Americans of different races, political affiliations and economic means bring varying levels of awareness and differing perspectives to the juvenile justice system. Research and everyday life experience shows us that some arguments or messages resonate more than others, and sometimes this depends on who the audience is. As many of your materials will have more than one audience, it is important to identify which messages translate best across different groups, as well as when and how to appropriately tailor messages to specific audiences.

- System Doesn’t Work: The fact that recidivism is so high is the strongest argument that the current juvenile justice doesn’t work well. Americans of all stripes respond strongly to the message that the system needs improvement because it fails to do what they want it to, which is to offer youth the rehabilitation needed to get and stay out of trouble with the law.

- Lens of Race: Our research reveals that African Americans perceive nearly every aspect of the juvenile justice system and youth prisons differently than white Americans do. Perceptions of the system’s fairness, concerns over conditions in youth prisons, beliefs about the root causes of the problems and what solutions are best are all impacted by race. This research did not find that the opinions of Latinos, Asians or other minority groups differed greatly from whites, and their opinions did not track with the strong reactions of African Americans.

- Awareness: Awareness of the juvenile justice system is low for many Americans, particularly among whites, Republicans and Independents. Most people’s opinions are shaped by what they see in the news and portrayals in popular culture, though African Americans are more likely to draw on personal experiences or those of their friends and families than whites.

- Perceptions of the Juvenile Justice System: Regardless of one’s level of familiarity, there is little sense within the public that the juvenile justice system has improved over the last 10 years, with perception of system failure especially acute among African Americans.

There is an opportunity to strengthen support in the key audiences of the public — in fact, it doesn’t take much convincing to make people understand the need for system reform. Our research identifies the strongest and weakest arguments to do so (see Know Your Message section for arguments). Furthermore, by understanding the impact that race has on one’s perceptions of the juvenile justice system, you can be more effective when speaking to audiences who are already invested in racial equity.

Arguments to Use and Lose

Some of these recommendations may surprise JDAI practitioners, but they have proven effective in shaping public opinion.

To appeal to audiences of mixed races, build an argument based on the concepts of rehabilitation and accountability

Research shows a universal belief that the main purpose of youth prisons should be to rehabilitate youth. The rate of recidivism is the most compelling data point for all audiences and should be used to build an argument that alternatives to detention and incarceration are more effective than confinement in protecting communities and changing the trajectories of kids’ lives for the better.

At the same time, the public believes in accountability. There is a consistent expectation among the American public that kids need to be held accountable for bad behavior, lest they continue to repeat those actions.

We realize that many juvenile justice experts and experienced system-level professionals believe that the majority of youth who get into trouble would be better served with little to no system exposure or intervention. Nonetheless, we advise that when specifically trying to move public audiences, avoid statements that seem to undermine the basic concept of holding youth accountable.

Messages for Arguments Based on Rehabilitation and Accountability

- Our juvenile justice system is not working and needs improvement.

- We can reinforce public safety by holding young people accountable and giving them the opportunity for rehabilitation.

- Today’s juvenile justice system focuses too much on punishment instead of rehabilitation. We know that sending kids to youth prisons does not rehabilitate them when 70% to 80% of youth are rearrested within two or three years of being released. Kids in youth prisons are denied the guidance, education and support network they need to reenter the community and become successful adults.

- The truth is any young person can make bad decisions. Some kids are misguided or troubled and some just find it hard to resist peer pressure. Whatever the cause may be, we have a juvenile justice system that favors kids with more financial resources and disadvantages racial and ethnic minorities. All kids, regardless of their race or financial situation, should face a fair system that advocates for them, not against them.

- We need to stop sending kids to youth prisons and replace incarceration with a better model that strengthens kids and families. There are successful alternatives to youth prisons that hold kids accountable, but also provide them with resources necessary to support their rehabilitation and give them a second chance and new opportunity.

Language to use and language to lose when talking about improving the juvenile justice system:

Race-Specific Messages

African Americans or advocates who are invested in race equity issues are far more attuned to arguments based on the concepts of fairness and justice, which also specifically highlight the system’s unequal treatment by race and economic status. When speaking to a public audience primarily made up of people of color and/or race equity advocates, tailor the broader message to also prioritize the concepts of fairness and justice.

Most effective arguments for African American audiences and/or race equity advocates

- Unequal treatment―economic: The juvenile justice system continues to deny many low-income youth nationwide the legal representation to which they are entitled under the Constitution, while those with financial means have stronger legal representation and even avoid entering the system altogether. This only increases the likelihood that low-income youth will both enter the system and end up in youth prisons.

- Unequal treatment―race: At virtually every stage of the juvenile justice process, youth of color―particularly Latinos and African Americans―receive harsher treatment than their white counterparts, even when they enter the justice system with identical charges and histories. More specifically, African-American youth are nearly five times as likely to end up in youth prisons as their white peers, and Latino and American Indian youth are between two and three times as likely to end up there.

Followed by:

- Success of alternatives: A number of alternatives to youth prisons have consistently improved the likelihood that youth involved in the justice system will go on to finish their education and lead productive lives with no decrease in public safety. These alternatives include helping young people with building family relationships, job training, mentoring programs, and community-based mental health, drug treatment and rehabilitation services. We can redirect young people who get into trouble with the law by providing them with a network of support that enables them to turn themselves around.

Messaging tailored to emphasize “Fairness” and “Justice”

Our juvenile justice system is not fair in its treatment of racial and ethnic minorities and needs improvement.

- Harsh punishment rather than rehabilitation works against public safety.

- Even young people in trouble with the law deserve to be treated fairly, and justice for them will ensure they get out of and stay out of trouble.

- Any young person can make bad decisions. Some kids are misguided or troubled and some just find it hard to resist peer pressure, but African Americans receive harsher treatment than their white counterparts. African-American youth are nearly five times as likely to end up in youth prisons as their white peers. All kids, regardless of their race, should face a fair system that advocates for them, not against them.

- Furthermore, our juvenile justice system focuses too much on punishment, instead of rehabilitation. We know that sending kids to youth prisons does not rehabilitate them when 70 to 80% of youth are rearrested within two or three years of being released. Kids in youth prisons are denied the guidance, education and support network they need to reenter the community and become successful adults.

- We need to stop sending kids to youth prisons and replace incarceration with a better model that strengthens kids and families. There are successful alternatives to youth prisons that hold kids accountable, but also provide them with resources necessary to support their rehabilitation and give them a second chance and new opportunity.

Arguments that don’t fare as well with the general public

- The Public’s Appreciation of Brain Science Arguments: The scientific fields of psychology, neurology, child development and others have produced compelling evidence to help us better understand the young brain. Their findings have influenced field practice and policy. There is evidence that decision makers — judges and policy makers — are influenced and even moved by the body of research that has explained how youth are different. But there is a lag in this information influencing the public. This is well-documented and reinforced by multiple studies that show that the public remains largely unaware, unconvinced and at times even hostile toward arguments that use brain science as evidence. JDAI’s peers in related fields — child welfare, foster care, family poverty — face the same challenge. Our research tested two brain development arguments, one focused on brain development and one on impulse control. While the percentage of people who found the arguments convincing are not bad, they are far behind the strongest arguments of successful alternatives, unequal treatment and the need for rehabilitation.

- “Decisions” v. Other Influences: The public is quite far apart from field experts in their appreciation of what motivates youth to get in trouble and take risks. The public is convinced that youth make “bad decisions” and that’s why they wind up in the system. Some in the field believe that youth don’t “think” at all; rather, they act on impulse, respond to peer pressure and have trouble with self-regulation. The data show that people are mixed on this. They think and talk about things like “impulse control” differently than the field experts. The public is more likely to believe that “kids do stupid things” and lack a supportive network to prevent them from making bad choices. It is important, however, to appreciate the differences between whites and African Americans, the latter of whom are more cognizant of social and environmental factors when it comes to why youth get into trouble.

JDAI Message Bank

The following set of messages will serve as a foundation for communicating about JDAI at large, including its core values, challenges and calls to action.

Basic Facts/Stats on State of Juvenile Justice

- Many Americans are misinformed or unaware that crime committed by youth is down by half over the last two decades.

- We are making progress. Public safety has increased while detention and incarceration of youth has decreased.

- Even with progress, the system is still failing kids. On any given day, about 50,000 youth are in secure confinement, but 62% of them have not committed serious or violent crimes.

- We know that sending kids to youth prisons does not rehabilitate them when 70% to 80% of youth are rearrested within two or three years of being released.

- Our system advantages white youth and is unfair to black and brown youth. African-American youth are nearly five times as likely to end up in youth correctional facilities as their white peers.

Introducing JDAI

- The JDAI network is a powerful platform for juvenile justice reform. The work of JDAI is urgent because despite our progress, too many youths are harmed and treated unfairly.

- For 25 years the JDAI network has been growing to serve 10 million youth across 39 states and 250 counties, including Washington, D.C.

- Today’s juvenile justice system focuses too much on punishment instead of rehabilitation. JDAI demonstrates that communities can both increase public safety and reduce the harmful practice of incarcerating young people.

- Achieving greater equity and outcomes for youth of color in the juvenile justice system is a priority of the JDAI network.

Key Challenges

- When youth get into trouble with the law, they face a system that favors kids with more financial resources and disadvantages racial and ethnic minorities.

- In spite of progress, we still are confining too many kids in detention, youth prisons and out-of-home placements.

- Harsh punitive policies don’t help youth change or make the public safer. If anything, youth placed in prison-like facilities are more likely to re-offend upon their release than their peers who avoided out-of-home placements.

- Isolating kids from their families and communities using confinement and probation has been proven not to work. We shouldn’t separate kids from the support they need to get back on track.

- An estimated 200,000 youth are tried, sentenced or incarcerated as adults every year across the U.S. According to decades of research, youth who are transferred from the juvenile court system to the adult criminal system are more likely to be re-arrested for a crime.

- The use of solitary confinement has long-lasting and devastating effects on youth, including trauma, psychosis, depression, anxiety and increased risk of suicide and self-harm. Many youth in solitary do not receive appropriate education, mental health services or drug treatment.

Progress

- Sites in the JDAI network have made a real difference in the lives of young people, their families and their communities by reducing detention by around 43% since their baseline year.

- JDAI has saved taxpayers by helping communities spend less to build and operate facilities that don’t work and hurt kids.

- More than 50 JDAI sites have closed detention units or whole facilities as a result of reducing demand, saving roughly $143.5 million per year.

- The JDAI initiative is working with sites’ local leadership to take on Disproportionate Minority Confinement (youth of color are detained at over three times the rate of white youth)

Youth Prisons

- Field leaders Patrick McCarthy, president and CEO of the Casey Foundation, and Vinny Schiraldi, senior research fellow directing the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management at Harvard Kennedy School, have stated:

- Every youth prison in the country should be closed and replaced with a better model.

- Youth prisons don’t work. They hurt kids, and there’s a better way.

- Youth in trouble are best served at home with guidance and support. For the few young people who need to be removed from home, we should provide small, homelike facilities near their families.

- Putting youth in prison does not increase public safety and it doesn’t help youth in trouble.

- Youth in trouble need education, guidance and a network of support in their community to get back on track.

Calls to Action Messages

- Youth prisons are no place for kids. Locking up youth has high costs and negative outcomes.

- We can do better. Closing youth prisons will enable reinvestment in more effective community-based alternatives to incarceration, and small, homelike secure facilities.

- Change is possible. Change at scale in closing youth prisons is possible without compromising public safety — several states have done so or are on their way.

- Most Americans are with us. People strongly favor rehabilitation, community-based programs and family supports over incarceration and youth prisons.