Summary

In December 2011, more than 100 of the nation’s leading juvenile justice experts convened for a day-long symposium in Washington, D.C., to remember and reconsider an historic reform campaign — the closure of Massachusetts’ entire network of juvenile reform schools in the early 1970s. The facility closures were unprecedented and highly controversial, and they were meticulously studied in their aftermath. For a time, many reformers believed that Massachusetts would become the model for similar efforts throughout the nation. However, a serious but time-limited spike in youth violence in the early 1990s prompted a dramatic turn away from rehabilitation and deinstitutionalization in juvenile justice, and the Massachusetts story largely faded from public consciousness.

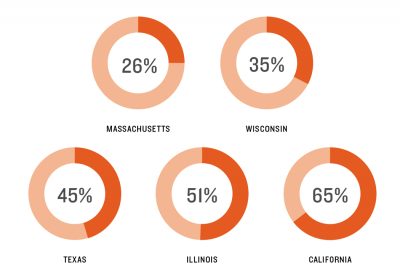

Recently, however, states across the country have begun shuttering juvenile corrections facilities and dramatically reducing the population of young people incarcerated. Suddenly, far from the one-of-a-kind anomaly it seemed only a few years ago, Massachusetts stands out today as a prescient trailblazer on the path to end our nation’s long-standing overreliance on juvenile incarceration. The symposium was convened to provide present-day reformers an opportunity to review the efforts of their predecessors in Massachusetts, glean the lessons of history and retool them for the current day.

This publication recounts the symposium. It provides a history of the Massachusetts reform campaign and its aftermath, summarizes the major themes and ideas presented by speakers and details the conclusions and recommendations emerging from group discussions.