Helping Savannah Youth Connect to Work, Avoid Confinement

Many Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative® (JDAI™) sites grapple with how to serve youth who are on a downward spiral toward confinement, for whom traditional alternative programming just doesn’t work. The juvenile court in Chatham County, Georgia, home to Savannah, initiated a new program for these young people — a program made possible by community investment and partnership.

Two Casey Foundation-supported community safety forums held a few years ago in Savannah, highlighted the need for innovative programming that could successfully serve youth at high risk of confinement. Acknowledging the benefits of keeping these young people at home, the juvenile court, in partnership with an array of local organizations, launched the Work Readiness Enrichment Program in the fall of 2017.

Savannah’s program was inspired by Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, a reentry program for formerly gang-involved and previously incarcerated men and women, many of whom share the same challenges as high-risk youth in Savannah’s juvenile justice system: pain from past trauma, lack of life skills, social disconnectedness. Savannah embraced some of Homeboy’s key attributes — staff members from participants’ own communities who have found success after facing similar challenges, a nonjudgmental desire to help individuals for whom other efforts have failed and programming that gives participants concrete skills.

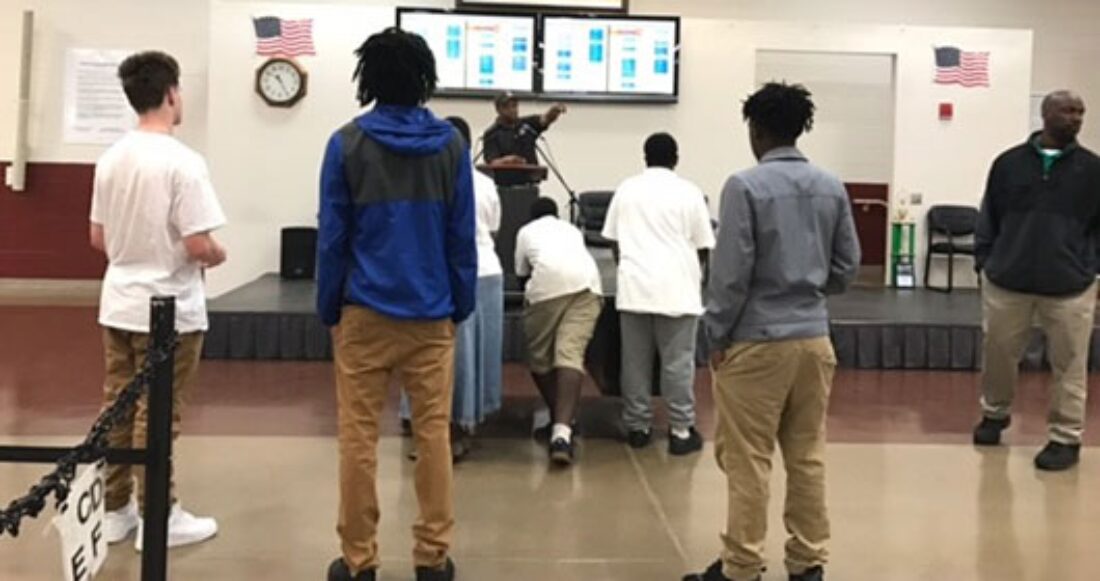

Now in the midst of its second cohort, the full-day Work Readiness Enrichment Program works with boys ages 14 to 16 who are struggling in multiple areas. Eligible youth have been charged with felony-level or multiple property crimes and are disengaged or significantly behind grade level at school. They are disconnected socially and haven’t responded to traditional programming. So far, 22 boys out of the 59 program-eligible youth have voluntarily participated in the eight- to 10-week program.

The program’s curriculum addresses a variety of skills and needs, made possible through a noteworthy collaborative effort among local government and community organizations. Each organization contributes its particular expertise and, in many cases, tangible assets:

- Chatham County Juvenile Court provides a program-dedicated probation officer, an educational advocate who helps youth transition back to school, meeting space — including a basketball court — and stipends for the youth.

- The Savannah-Chatham County Public School System provides a full-time teacher, a part-time special education expert, its online credit recovery program, laptops and bus passes.

- Goodwill Southeast Georgia teaches work readiness skills, including how to create a resume and fill out a job application, and connects older youth to potential job opportunities.

- Frank Callen Boys and Girls Club provides gang interventionists to lead fatherhood and parenting classes.

- Heads Up Guidance Services hosts group behavioral health “circles” where boys discuss topics such as anger management and coping mechanisms.

- YMCA of Coastal Georgia teaches financial literacy fundamentals for teens, including budgeting and how to avoid common financial mistakes.

- America’s Second Harvest of Coastal Georgia, a local food bank, provides free lunches.

“I’ve never seen this type of collaboration,” says Deputy Court Administrator Alisha Markle. “There is a genuine interest in helping these youth, a strong desire to make the community better.” This interest is not lost on the young people in the program, who say they feel loved and treated with respect by staff members who “listen to us for real.”

Ultimately, the county aims to extend the program to 18 weeks, hopefully helping youth to sustain improvements seen after the short eight-week pilot program last fall. Improvements include achieving educational gains; increasing leadership skills; recovering sufficient credits to return to school on or closer to grade level; and taking advantage of more healing support.

“These kids are thirsty for connection, for skills,” says Casey Foundation Senior Associate Tanya Washington. “At the beginning of the pilot, they wouldn’t look you in the eye. At the end, we had boys eager to remain in the program this spring. Five did remain, returning to school and holding onto jobs. They felt a new sense of self-worth and had hope for their futures.”