Who Are Opportunity (Disconnected) Youth?

The KIDS COUNT® Data Center, which tracks trends among youth ages 16 to 19, indicates that 7% of the nation’s older teens — more than 1.2 million young people — are neither working nor in school, according to the latest data from 2024. While national rates have improved since a peak of 9% in the previous decade, more than a million older teens remain disconnected, with substantial differences across states and demographic groups. These teens are sometimes called “disconnected youth,” but the term “opportunity youth” is increasingly preferred, as it reflects their potential to thrive when given access to the right supports.

Many leading organizations include ages 16 up to 24 when defining opportunity youth, recognizing that adolescent development continues into young adulthood. When ages 20 to 24 are included, an additional three million young adults are disconnected from work and school, underscoring the need to ensure youth are well-supported before they reach adulthood.

Opportunity youth often come from communities with higher levels of poverty or limited resources. Many have disabilities or have experienced homelessness, child welfare involvement or contact with the juvenile justice system. Youth of color are also disproportionately represented in this group. It is essential to understand how you measure disconnected youth, as consistent definitions and data help states and communities identify gaps and ensure that young people receive meaningful pathways to education and employment. (The KIDS COUNT Data Center provides definition and source details on every data page.)

Why Focus on Opportunity Youth?

When compared to peers who are in school or working, opportunity youth are more likely to experience a range of challenges in adulthood, such as employment difficulties, low incomes and poor physical and mental health. Conversely, youth who stay engaged with education and employment gain experience and qualifications to obtain good jobs, earnings, health care and other resources. Stable, caring relationships with adults are also key to helping young people navigate the hurdles of school, work, finances and life as they transition to adulthood.

The economic effects of opportunity youth extend to society as a whole. For example, a single person who is disconnected during their youth can lead to $1 million in societal costs due to lost wages, tax revenues and other issues.

Systemic inequities — such as unequal access to quality schools, safe housing and community resources — contribute to youth disconnection, particularly among young people in under-resourced communities. Prevention efforts to support children before they are struggling and early intervention programs that provide mentoring, training and wraparound supports can help prevent disconnection and keep young people on pathways to education and employment.

Tracking trends related to opportunity youth provides information on how the nation is faring and which locations across the country are providing equitable access to education and employment opportunities.

What Are the Causes of Youth Disconnection?

Several factors contribute to youth disconnection, and understanding these root causes can help communities better support young people.

Examples of such factors include:

- Limited access to quality education: Unequal school funding, transportation barriers and fewer advanced learning opportunities can contribute to youth disconnection by reducing students’ ability to stay engaged and on track toward graduation.

- Economic hardship and neighborhood conditions: Higher levels of poverty, unstable housing and limited local job options make it harder for young people to secure employment or remain in school, increasing the risk of disconnection.

- Health and mental health challenges: Disabilities, including physical, mental or cognitive health conditions or related needs — including stress and trauma — can interfere with attendance, learning and employment, leading some youth to lose connections to school and work, especially if these issues go unaddressed.

- Child welfare or juvenile justice involvement: Young people involved in these systems often experience disrupted schooling and fewer transition supports, which can contribute to youth disconnection.

- Lack of supportive adult relationships: When youth do not have stable, caring adults to help them navigate school, work and life transitions, they face greater barriers to staying connected to opportunity.

A large body of literature describes additional factors that may contribute to youth disconnection, including labor market trends, cultural shifts, structural forces, young parenthood and more. However, more research is needed to fully understand the root causes of this issue.

Opportunity Youth in America: Data and Trends

The share of U.S. teens ages 16 to 19 who are not working or in school has remained fairly steady, around 7%, over the last decade. However, this still means that more than one million teenagers remain detached from school and work and need support in order to re-engage in these settings. This is in addition to three million young adults ages 20 to 24 who are disconnected from education and employment, as well.

At the same time, the share of unemployed teens ages 16 to 19 improved during much of the last decade, dropping from 71% in 2014 to 64% in 2022 — since then, however, this rate inched up to 66% by 2024. The progress through 2022 suggests that youth had been increasingly engaged in the workforce, but the latest data indicate this trend may be reversing.

For more than two decades, the KIDS COUNT Data Center has also tracked U.S. teens ages 16 to 19 who are neither in school nor high school graduates, called the “status dropout rate.” This measure reveals a positive long-term trend, with the status dropout rate falling from 11% in 2000 to 4% in 2012 and holding steady at that level through 2024.

While these trends present a mixed picture, one finding is clear: a consistently large group of teens continue to need support re-engaging in school and work pathways. The overall findings also mask substantial disparities by geography and race.

Opportunity Youth Stats by Region, State, Congressional District and City

Rates of opportunity youth vary across the country, with higher levels in rural Western states and parts of the South and lower rates across much of the Northeast and Midwest, according to the latest data. Youth in historically marginalized communities also experience higher disconnected rates due to limited access to quality education, employment opportunities, transportation and other supportive resources, as described above.

Regional Snapshot (Ages 16–19, 2024)

| Region | Average Youth Disconnection Rates | Range |

|---|---|---|

| West | 8% | 5–11% |

| South | 7% | 5–10% |

| Midwest | 6% | 4–8% |

| Northeast | 5% | 3–6% |

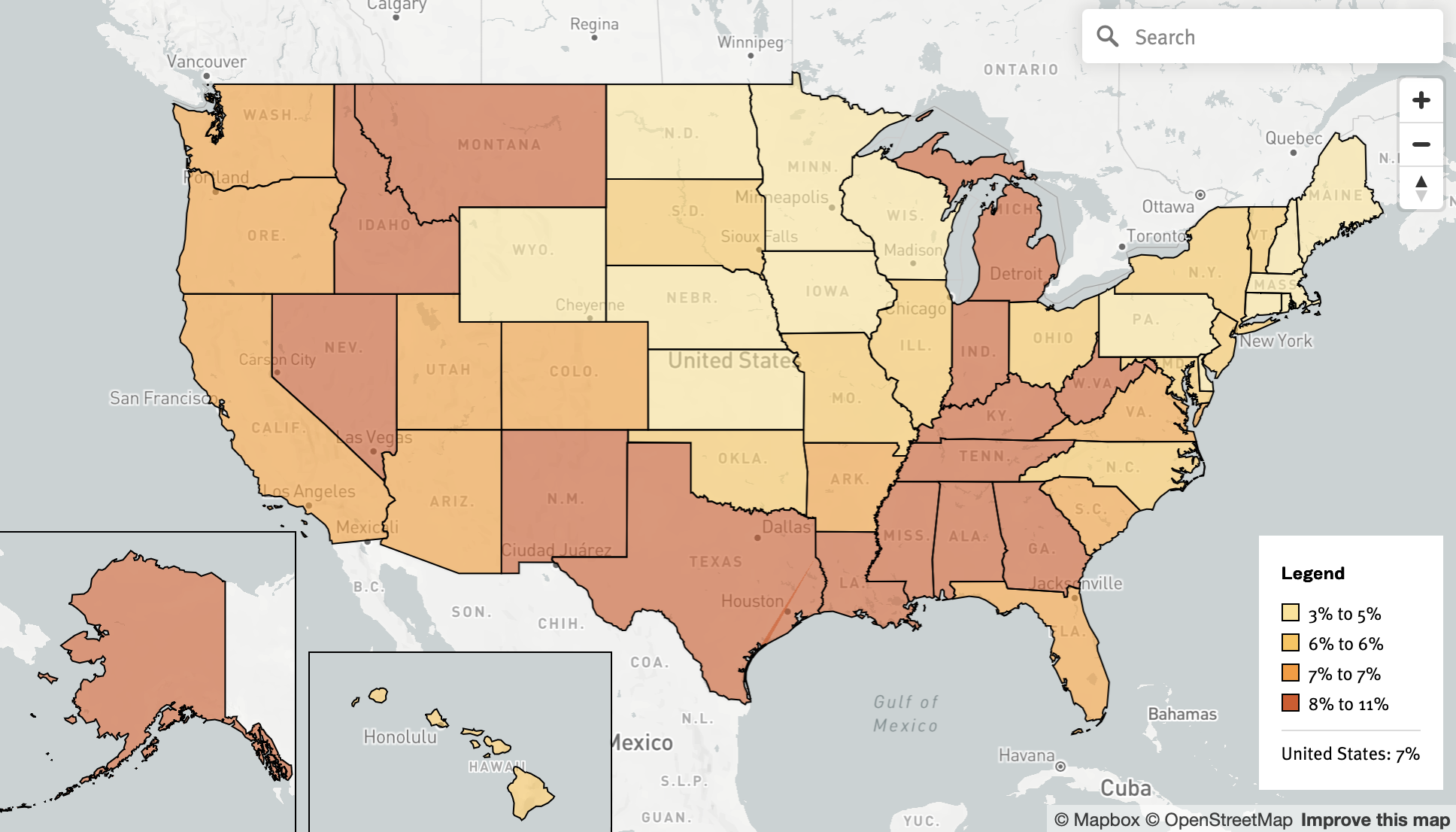

- By state: Data at the state level show wide variation, with some states experiencing more than double the disconnection rates of others. In 2024, the highest percentages of opportunity youth were found in Alaska (11%), Mississippi and Nevada (both 10%). Massachusetts had the lowest share of teens neither in school nor working that year, at 3%. Between 2023 and 2024, this rate improved in 12 states and worsened in 16.

Teens Ages 16 to 19 Not Attending School and Not Working (Percent) 2024

Full state-by-state disconnected youth data are available through the KIDS COUNT Data Center.

- By U.S. congressional district: Two congressional districts in the West and upper Midwest had the highest shares of opportunity youth in 2024. More than 1 in 6 (17%) older teens were disengaged from both work and school in Michigan’s Congressional District 13 (including parts of Detroit and its suburbs), and the same was true for more than 1 in 7 youth (15%) in California’s Congressional District 22 (in the San Joaquin Valley). The congressional districts with the lowest shares of opportunity youth in 2024 — just 2% of teens — were in Illinois’ Congressional District 8 (just northwest of Chicago), North Carolina’s Congressional District 4 (central state, including Durham) and Minnesota’s Congressional Districts 2 and 6 (southeast region, near the Twin Cities).

- By city: Among the 50 most populous U.S. cities with available data in 2024, the greatest share of opportunity youth were in Bakersfield, California and Memphis, Tennessee (both 14%). The cities with the lowest shares of opportunity youth that year were also in California: San Jose and San Diego (both 3%).

Enduring Inequities for American Indian or Alaska Native, Latino and Black Youth

The KIDS COUNT Data Center has tracked opportunity youth by race and ethnicity for 15 years, from 2008 to 2023 (the most recent year on the site). Over this time frame, American Indian or Alaska Native, Black and Latino teens consistently had higher rates of disconnection from school and work when compared to teens nationwide. One in 10 American Indian or Alaska Native youth across the country were neither working nor in school in 2023. Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander teens and young adults are also disproportionately represented among opportunity youth.

Similarly, in over two decades from 2000 to 2023, the KIDS COUNT Data Center found that American Indian or Alaska Native and Latino teens, ages 16 to 19, had higher status dropout rates (i.e., neither in school nor high school graduates) compared to the national average.

These findings point to ongoing structural inequities in access to high-quality education, workforce opportunities and related resources — such as counselors, school and community support services and out-of-school-time programs — that can help youth stay engaged.

Supporting Opportunity Youth

Policymakers and leaders from multiple sectors can take steps to reduce inequities and keep youth engaged in school or work, including:

- Providing access to affordable, accessible high-quality early childhood education, especially in low-income communities, sets the stage for academic success and decreases disparities by income and race.

- Providing equitable access to high-quality K–12 education, including ensuring that schools in low-income areas have adequate resources, counselors and support services as well as positive environments and non-punitive discipline policies.

- Strengthening early-warning systems in schools and communities to identify youth who are struggling and to connect them with needed support, whether related to academics, disabilities, family issues, health care, mental health or other needs.

- Ensuring that flexible learning experiences are available and tailored to youth needs and that schools offer strong support for the transition from middle to high school and high school to postsecondary pathways, especially in areas with higher rates of youth disconnection.

- Increasing access to youth development programs — such as mentoring, after-school and civic engagement — helps youth form relationships with supportive adults and meaningfully contribute to their community.

- Providing equitable access to high-quality employment opportunities, such as internships, apprenticeships and career and technical training programs.

- Creating targeted plans to address the unique needs of communities with high rates of opportunity youth.

For the millions of young adults who are disconnected from work and school, leaders can also invest in efforts to address specific barriers for this group, such as financial support for good child care so young parents can work or help with transportation to job training programs. Additionally, job programs should be designed to prepare young people for high-quality, in-demand positions with adequate wages, benefits and growth potential.

As a recent RAND article described, “…there is no one-size-fits-all solution for disconnected youth; rather, the wide variety of experiences and needs among disconnected young people call for a variety of solutions.”

More Resources on Supporting Opportunity Youth

- See all data on youth and young adults in the KIDS COUNT Data Center, including more than 60 indicators related to employment, poverty, education, health, mental health and family and community issues

- Access these publications:

- Thrive: How the Science of the Adolescent Brain Helps Us Imagine a Better Future for All Children, Lisa M. Lason, president and CEO of the Annie E. Casey Foundation

- Career Pathways to Success: Supporting Young Adults in Education and Employment, Annie E. Casey Foundation

- Creating Equitable Ecosystems of Belonging and Opportunity for Youth, Forum for Youth Investment

- Insights From a Pandemic, Johns Hopkins University’s Everyone Graduates Center

- Tipping the Scale, Jobs for the Future

- Community-Based Workforce Engagement Supports for Youth and Young Adults Involved in the Criminal Legal System, Urban Institute.

Sign up for our newsletters to get the latest data, reports and resources