Child Well-Being in Single-Parent Families

This post highlights the latest statistics and demographic trends involving children in single-parent families. It identifies some common hurdles facing these families and shares opportunities for supporting both single parents and their children.

Defining Children in Single-Parent Families

The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s KIDS COUNT® Data Center uses U.S. Census Bureau data to define children in single-parent families. This demographic group describes any child under age 18 who lives with an unmarried parent. Children living with cohabiting couples are included in this group, but children living with married parents and stepparents are not.

Statistics About Children in Single-Parent Families

In the United States today, more than 23 million children live in a single-parent family. This total, has risen over the last half century and currently covers about one in every three kids across America. A number of long-term demographic trends have fueled this increase, including: marrying later, declining marriage rates, increasing divorce rates and an uptick in babies born to single mothers.

Within single-parent families, most children — 14.3 million — live in mother-only households. More than 6 million kids live with cohabiting parents and about 3.5 million kids live in father-only households, according to 2022 estimates.

Among unmarried parents, the share of single mothers has shrunk in recent decades while the share of cohabiting parents has grown.

Statistics by Race, Ethnicity and Family Nativity

The likelihood of a child living in a single-parent family varies by race, ethnicity and family nativity. Research indicates that differences by race and ethnicity are tied to socioeconomic status, discussed in more detail below. Data from 2022 indicates that:

- Black and American Indian or Alaska Native kids are most likely to live in single-parent families with 63% and 50% of these children, respectively, fitting this demographic.

- White (24%) and Asian and Pacific Islander (16%) kids are least likely to live in a single-parent household.

- Latino children and multiracial kids fall in the middle — with 42% and 39% of kids from these groups, respectively, living in a single-parent family.

Family nativity also makes a difference. Children in immigrant families are more likely to live with married parents than their peers in non-immigrant families. This has been true since the KIDS COUNT Data Center began tracking this measure in the early 2000s. In 2022, more than a third (37%) of kids in U.S.-born families lived in a single-parent household compared to just a quarter (25%) of kids in immigrant families.

Single-Parent Family Differences by State, City and Congressional District

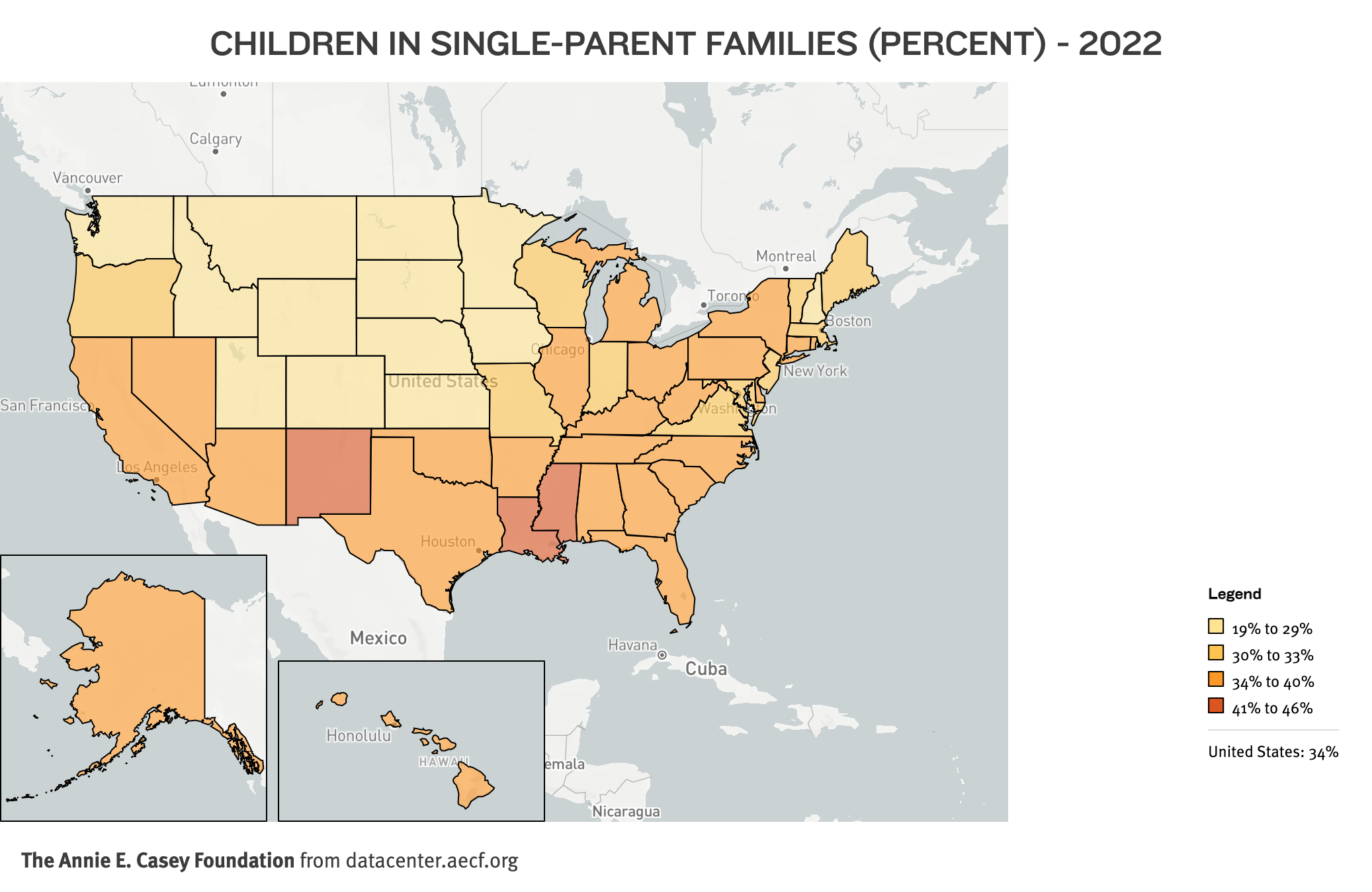

The likelihood that a child lives in a single-parent family varies by location.

At the state level, this statistic varies — from about one in five (19%) kids in Utah to almost half (46%) of kids in Louisiana living in a single-parent household.

Among the 50 most populous U.S. cities with data in 2022: The share of children in single-parent families ranged from one in four (25%) in San Francisco to more than two-thirds (71%) in Detroit. The KIDS COUNT Data Center also provides this by Congressional District, which indicates even greater variation locally — from a low of 14% inNew Jersey’s District 11 to a high of 65% in New York’s District 15.

Statistics on Single-Parent Homes and Poverty

Family structure and socioeconomic status are closely linked, according to decades of research. Increasingly, marriage reflects a class divide, as individuals with higher incomes and education levels are much more likely to marry. In 2022, nearly 30% of single-parent families lived in below the federal poverty level while just 6% of married-couple families. Single parents are also more likely to live in poverty when compared to cohabiting couples, and single mothers are much more likely to be poor compared to single fathers.

Common Challenges of Single-Parent Families

A number of factors have fueled the rise in single-parent families. For instance: More people are opting to marry later in life, skip marriage altogether and have kids outside of marriage. At the same time, marriages have grown more likely to end in divorce.

More than 20% of children born to married couples will experience a divorce by age 9 and more than 50% of kids born to cohabiting couples will experience a parental breakup, according to some estimates.

Major changes in parental relationships, such as transitioning from a two-parent to a single-parent household, can disrupt a child’s routines, education, housing arrangements and family income. It can also add parental conflict and stress. These changes can be very difficult — and even traumatic — for some children.

Compared to kids in married-parent households, children in single-parent families are more likely to experience poor outcomes. Research indicates that these differences in child well-being tend to be small, though, and can disappear when adjusting for key factors like poverty. While the research is complex, sometimes contradictory and evolving, mounting evidence indicates that underlying factors — such as strong and stable relationships, parental mental health, socioeconomic status and access to resources — have a greater impact on child success than does family structure itself.

Children thrive when they have safe, stable and nurturing environments and relationships, and these conditions and connections can exist in any type of family.

Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Its Impact on Children

Single-parent families — and especially mother-only households — are far more likely to live in poverty compared to married-parent households. Given this, kids of single parents are more likely to experience the consequences of growing up poor. Children in poverty are more likely to have physical, mental and behavioral health problems, disrupted brain development, shorter educational trajectories, contact with the child welfare and justice systems, employment challenges in adulthood and more.

Many families are low-income but sit above the federally-defined poverty line. Children from these families are also more likely to have poor life outcomes compared to those in higher-income families. Additionally, low-income kids (below or above the poverty line) often live in less safe communities with limited access to quality health care, support services and enriching activities — all of which influence their ability to thrive.

Researchers have also linked poverty to parental stress. Single parents may struggle to cover their family’s basic needs, including food, utilities, housing, child care, clothing and transportation. Navigating these struggles alone — and with limited resources — can send stress levels soaring. High parental stress, in turn, can spark even more challenges and adverse outcomes among the children involved.

Also worth noting: Poverty levels for Black, American Indian or Alaska Native and Latino children are consistently above the national average, and these generations-long inequities persist regardless of family structure.

Potential Emotional and Behavioral Impact on Children

While most children in single-parent households grow up to be well-adjusted adults, kids from single-parent families may be more likely to face emotional and behavioral health challenges — like engaging in high-risk behaviors — when compared to peers raised by married parents. Research has linked these challenges with factors often associated with single-parent families, such as parental stress, parental breakups, witnessing conflict, lost social networks, moving homes and socioeconomic hurdles.

Children of single mothers may face additional challenges. For instance: Depression, which can negatively impact parenting, is common among recently divorced mothers. Solo moms often lack adequate social support and can face social stigma, as well.

Such hardships would be difficult for any child. But kids can recover and thrive — particularly when raised with the benefits of nurturing relationships, stability, and mental health support.

Potential Impact on Child Development

Experts increasing view child development disruptions through the lens of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). These potentially traumatic events can take many forms, such as divorce or parental separation, poverty, experiencing mental health challenges or , substance abuse at home, exposure to violence, and so forth. ACEs can cause“toxic stress,” which can lead to lasting, deleterious consequences on a child’s physical and mental health, education and other life outcomes.

The risk of ACE exposure varies by a child’s race and ethnicity, with American Indian or Alaska Native and Black children more likely to experience multiple ACEs than peers from other racial and ethnic categories. Generally speaking, however: The more ACEs a child experiences, the greater the risk of harmful effects, regardless of family structure.

Potential Influence on Education

Academically speaking, children in single-parent families are more likely to drop out of high school when compared to peers with married parents. This heightened risk is likely due to factors associated with many single-parent households; research indicates that children fewer economic, social and parental resources, more family instability, and more ACEs are at increased risk of poor educational outcomes — including dropping out of school.

Changes in Time Spent with Parents

While every family situation is unique, children in single-parent households are likely to have less time with their parent when compared to peers in cohabiting- or married-couple households. This is particularly true if that parent works more than one job or long hours to make ends meet.

After a divorce or parental breakup, children often have less time with their nonresident parent, which is typically the father. Maintaining an involved, nurturing relationship with the noncustodial parent is highly important for a child’s well-being.

A Better Infrastructure and Stronger Safety Net for Families

Many program and policy strategies exist to support children in single-parent families and to reduce inequities due to race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. For example, outcomes for these children can be improved by:

- Strengthening financial and health care safety net programs and improving affordable housing, which can reduce instability and parental stress.

- Providing affordable, accessible high-quality early childhood education, which has critical benefits for child development and supports parental employment and family stability.

- Maximizing two-generation community development strategies that improve the quality of equitable opportunities for quality education for kids while building job and parenting skills for the adults in their lives. Also, promoting policy changes to ensure that full-time jobs pay enough to cover basic needs and offer paid family leave, which has been shown to improve parent and child health.

- Supporting the needs of young parents and also young fathers, especially those of color.

- Offering trauma-informed and culturally appropriate services — such as home-visiting services, parent education, mental health care and substance use treatment — that address parental stress and support family relationships.

- Improving access to trauma-informed and culturally responsive services — such as home-visiting services, parent education, mental health care and substance use treatment — that address parental stress and support family relationships.

- Addressing institutional racism across public and private sectors, including health care and education, to expand equitable access to quality services and other resources.

Strengths of Single-Parent Families

Many single parents provide stable, loving environments and relationships for their children. Examples of how single-parent families can benefit children include:

- Solo parents may have more time to focus on their kids if they no longer need to spend time focusing on the needs of their spouse or partner.

- Years of fighting may precede a divorce or separation. Ending this conflict and providing calm home environments is important for children and can reduce stress for the entire family.

Changing the Conversation About Children in Single-Parent Families

Children can thrive in any family structure, and family structures often change over time. Family types have also become more diverse, with blended step-families, same-sex parent families, children living with relatives and more. Children’s relationships to their parents or caregivers may be biological, adoptive, step, kin, foster care or other. It is increasingly important to recognize the diversity of family compositions rather than discussing them as only two or three groups.

In addition, single parents who choose to have kids through donors or surrogacy may not have the same socioeconomic disadvantages, lack of support or parental stress associated with other single parents. As we think about family structure and single-parent families, it may be helpful to keep in mind these nuanced and evolving issues.

For many years, the conversation among researchers, advocates, policymakers and others regarding single-parent families has focused on how this family type might negatively affect children. What if, instead, we focus on what children need to thrive?

We know that all young people — including kids in single-parent families — flourish when they have caring, committed relationships with parents or other loving caregivers. We also know the importance of safe, stable homes, communities and families that have adequate socioeconomic resources, social supports and services. Focusing on quality-of-life experiences and ensuring equitable access to opportunities can help young people reach their full potential.

Learn More About Vulnerable Families and Stay Connected

For decades, the Annie E. Casey Foundation has promoted the well-being of vulnerable children and youth, including those in single-parent families and in poverty. The Foundation has tracked data, published resources, supported programs and advocated for policies to improve the lives of these children, youth and families. Explore the Foundation’s many publications, tools and best practices, blog posts and other resources, such as:

- Report: Developing Two-Generation Approaches in Communities

- Report: Opening Doors for Young Parents

- Blog Post: Thrive by 25 Announcement

- Strategies: Economic Opportunity

- Resources: Fatherhood

- Resources: Child Poverty

- Resources: Earned Income Tax Credit

- Resources: Racial Equity and Inclusion

- Resource: KIDS COUNT Data Book

Sign up for our newsletters to get the latest reports and resources