Communities With Limited Food Access in the United States

What Is a Food Desert?

Neighborhoods with limited food access — sometimes called “food deserts” — are geographic areas where residents have few to no convenient options for securing affordable and healthy foods, especially fresh fruits and vegetables. Neighborhoods with limited access to high-quality food can create extra, everyday hurdles that make it harder for kids and families to grow healthy and strong. When people have better access to supermarkets, for example, they are more likely to have nutritious diets and lower rates of chronic disease, according to research.

Redefining Food Deserts: Evolving the Language Around Food Access

Experts, researchers and government agencies are increasingly recognizing the limitations of the term food desert when referring to neighborhoods with limited food access. Among the limitations identified, the term:

- suggests that the primary problem is about the physical environment, such as distance to food, rather than intentional decisions that have led to limited grocery stores in low-income communities;

- neither acknowledges nor captures other aspects of the issue, such as food affordability, store hours and cultural acceptability of food;

- does not acknowledge food quality and the high prevalence of unhealthy foods in convenience stores in urban, low-income neighborhoods; and

- is deficit-oriented and doesn’t take into account the ability to get groceries online or other resilient food access strategies, such as farmers markets and community gardens.

More descriptive, thoughtful language can help promote solutions that go beyond the built environment and address underlying issues. At the same time, since “food desert” is still the most commonly used short-hand phrase, this post uses that term along with more descriptive language.

Where Are Food Deserts in America?

Among the states with the greatest share of residents living in low-income, low-food access areas (formerly called “food deserts”) in the United States, nine of the top 10 are located in the South, according to a 2025 analysis of historical data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Access Research Atlas. Mississippi ranks first, with 30% of its residents living in these neighborhoods, followed by 29% of New Mexico’s population and 26% of Arkansas’s population. States in the Northeast, including New York (4%), Rhode Island (5%), Vermont (5%) and New Jersey (5%),

are among the least likely to have residents living in areas with limited food access.

Among large metropolitan areas, 32% of the residents in Memphis were classified as living in low-income communities with limited access to healthy food, according to a 2021 USAFacts analysis of the same USDA data. No other large metro city had a greater share of its population affected. One local nonprofit is fighting back with a 44-foot-long refrigerated trailer. Called The Mobile Grocer, this mini supermarket-on-wheels travels to different neighborhood food deserts. It arrives packed with affordable groceries — including fresh produce — and helps to feed thousands of Memphis residents each week.

San Antonio was home to the nation’s second-highest rate of residents living in low-income communities with insufficient food access (26%, tied with Riverside, California). The city’s Healthy Corner Store Program is partnering with small neighborhood corner stores to address this issue. Today, the program spans a network of over 45 stores working to fill in San Antonio’s grocery gaps.

Generally speaking, limited access to food is more common in:

- communities with higher rates of poverty, whether rural or urban;

- neighborhoods with greater shares of people of color; and

- rural American Indian or Alaska Native communities.

A 2022 study examined U.S. census tracts by race and ethnicity, poverty level and access to quality food stores. It found that high-poverty, non-white — particularly Black — neighborhoods continue to have the least access to supermarkets.

Further, a 2023 analysis found that, in the most remote parts of the country, American Indian and Alaska Native populations were heavily over-represented in areas with limited supermarket access.

How Are Communities Identified as Food Deserts in the United States?

Researchers consider a variety of factors when identifying these neighborhoods, including:

- access to healthy food in local stores, as measured by distance to supermarkets or large grocery stores or by the number of stores in an area;

- household resources, including family income and/or vehicle availability; and

- neighborhood resources, such as the average income of residents and the availability of public transportation.

The USDA identifies such communities as “low-income, low-access” census tracts, according to the following definitions:

- Low-income census tracts: poverty rate of at least 20% or a median family income at or below 80% of the statewide or metropolitan area median family income.

- Low-access census tracts: At least 500 people or 33% of residents live more than one mile in urban areas or more than 10 miles in rural areas from the nearest supermarket or large grocery store. (The USDA measures access using other distances as well.)

The overlapping low-income and low-access census tracts represent communities with the greatest potential difficulties in obtaining nutritious food. The USDA also measures household vehicle access, a key factor that can overcome access barriers for people living far from grocery stores. However, the analysis does not take into account other possible sources of food, such as farmers’ markets or food pantries, and it does not assess the quality or affordability of available food in these census tracts

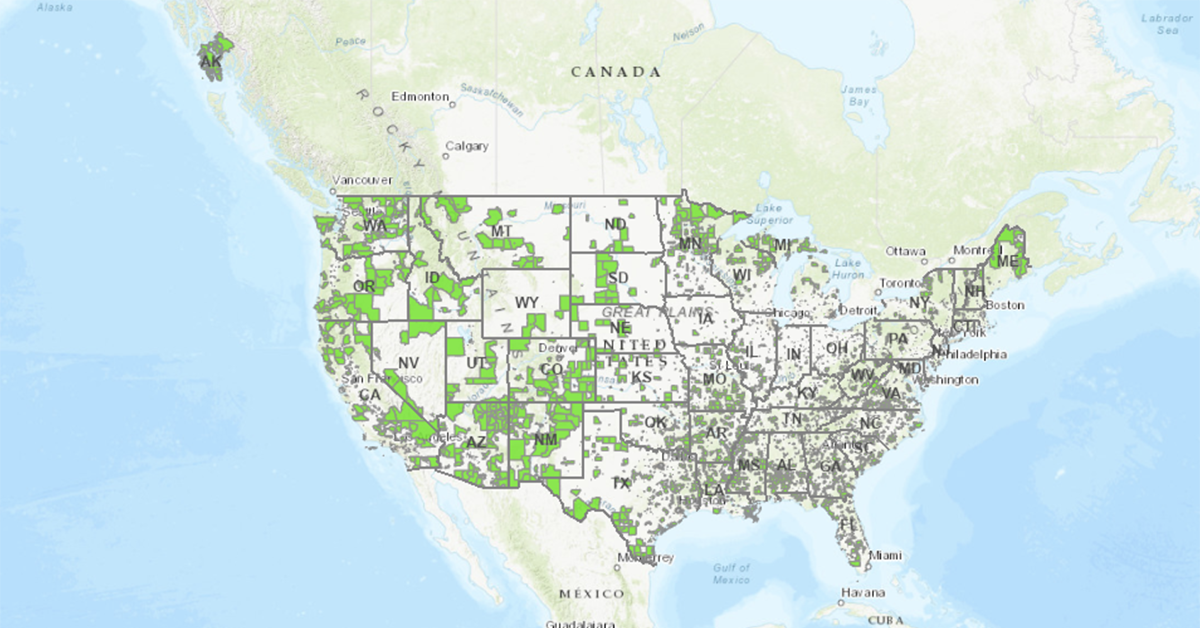

Mapping Low-Income, Low-Access Areas in the United States

Source: USDA Food Access Research Atlas, Low Income and Low Access Layers, 2019

How Many Americans Live in Neighborhoods Facing Inadequate Food Access?

About 39 million people — 13% of the U.S. population — were living in low-income and low-access areas, more than 1 mile (urban) or 10 miles (rural) from the nearest supermarket or large grocery store, according to the USDA’s most recent food access research report, published in 2022.

Within this group, researchers estimated that almost 19 million people — or 6% of the nation’s total population — had limited access to a supermarket.

What Causes a Food Desert?

There is no single cause, but there are several contributing factors.

The Food Distribution System

Our country’s system has generally resulted in low-income communities having a higher concentration of small corner stores, convenience markets and fast food vendors, with fewer healthy food options. Low-income families are more likely to live in these neighborhoods, also called “food swamps,” overloaded with convenience foods.

Supermarket Disinvestment

Some communities have experienced intentional disinvestment, with chain supermarkets locating in wealthier suburbs instead of lower-income urban neighborhoods. While some attribute this to market self-regulation, recognizing that opening a store in a low-income area may have real or perceived investment risks, research shows this pattern is not solely due to commercial factors.

Transportation Challenges

Low-income families are less likely to have reliable transportation (either a personal vehicle or the ability to pay for transportation), which can prevent residents from traveling where needed to buy nutritious groceries. A lack of public transportation infrastructure also can be a barrier for low-income families to obtain food.

Income Inequality

Healthy food costs more. When researchers from Brown University and Harvard University studied diet patterns and costs, they found that the healthiest diets — meals rich in vegetables, fruits, fish and nuts — were, on average, $1.50 more expensive per day than diets rich in processed foods, meats and refined grains. For families living paycheck to paycheck, the higher cost of healthy food could make it inaccessible even when it’s readily available.

How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact Food Deserts and Access to Nutrition?

The coronavirus pandemic injected even more challenges — both logistical and financial — into the complex field of food access. At the same time, insights were gained that could help inform future strategies for improving access to food.

As COVID-19 cases rose across the country, restaurants, corner stores and food markets — among other businesses — closed their doors or reduced their operating hours. Residents who relied on public transportation for fetching groceries faced additional hurdles, including new travel restrictions and scaled-back service schedules. Further, the pandemic led to supply chain disruptions, increased unemployment, reduced family income and lost access to school meals for kids, fueling an increase in food insecurity rates in 2020.

Pandemic-relief measures, such as the expanded Child Tax Credit, helped to reduce child poverty and food insecurity rates in 2021. But this positive trend reversed course when these measures expired, and both child poverty (according to the Supplemental Poverty Measure) and food insecurity rates spiked in 2022 and 2023 and 2023. Many experts point to the success of these pandemic-era policies as evidence of what works to strengthen family financial and food security.

Additionally, during the pandemic, online grocery (e‑grocery) shopping increased by more than 100%. Researchers also note that smartphone ownership is rapidly rising among low-income populations, indicating that e‑grocery options may be a promising direction for expanding food access among groups with barriers to traditional in-person stores. A variety of digital solutions are now being studied.

What Are the Solutions to Combat Food Deserts in America?

Federal, state and local policy solutions are needed to address inadequate and inequitable access to high-quality food. Beyond policies, other forces — including economic, commercial, environmental, cultural, community and individual — shape food access and eating patterns. Within this complex landscape, some strategies for alleviating poor food conditions include:

- partnering with residents to determine community-driven solutions, from data collection and policy development to program planning and interventions;

- extending support for small, corner-type stores and neighborhood-based farmers markets to increase the availability and affordability of healthy foods in under-resourced areas;

- strengthening food production and distribution practices and policies, such as building infrastructure for urban agriculture, improving food procurement standards and supporting local food-based businesses, e.g., cooperatively-owned stores;

- supporting food sovereignty models, in which residents oversee their own food production and distribution processes, particularly in American Indian and Alaska Native communities;

- incentivizing large grocery stores and supermarkets in underserved areas;

- promoting community programs to encourage healthier eating;

- ensuring that community food pantries are effectively implemented;

- increasing access to and strengthening federal food assistance programs — such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), WIC and school meals — which provide critical relief for children and families facing hunger;

- incentivizing or requiring small grocery stores and farmer’s markets to accept SNAP Electronic Benefit Transfer payments and WIC; and

- continuing to explore innovative food access strategies through mobile apps, digital solutions or other possibilities.

While the specific solutions will look different in every community, multidisciplinary partnerships and long-term commitments will be needed to improve equitable access to healthy food.

Casey Foundation Resources on food Insecurity and Food Access

- Child Food Insecurity in America, 2024

- 41.5 Million People Received Food Stamps in 2021

- Most Common Uses of 2021 Child Tax Credit Payments: Food, Utilities, Housing, Clothes

- Economic Opportunity Resources and Strategies

- Child Poverty Rates Remained High in 2023: At Least 10 Million Kids in Poverty

KIDS COUNT® Data Center Resources Related to Food Insecurity

Other Resources on Food Access

- Food Policy Resources, Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future

- Healthy Food Access Portal

- Healthy Food Policy Project

Sign up for our newsletters to get the latest data, reports and resources