What Juvenile Justice Data Reveal — And What the Numbers Can’t Tell Us

Tom Woods

Tom Woods

When the subject is youth crime, trends and data don’t paint a complete picture. For anyone who lives in a community that has experienced high rates of crime for generations, there’s not much comfort hearing that things used to be 50% worse. Youth crime isn’t something that can be described by abstract numbers on a chart — especially when it has touched you personally.

However, when we think about how government and society should respond to crime, especially crime committed by young people, trends do matter. They ground us in facts and give us context to help make sense of this moment and lean into proven solutions.

What the Data Tell Us

There’s no perfect measure of youth crime, but we can look at several indicators, such as:

- crimes reported to the police;

- arrests;

- court referrals;

- detention admissions;

- self-reported crimes; and

- victimizations.

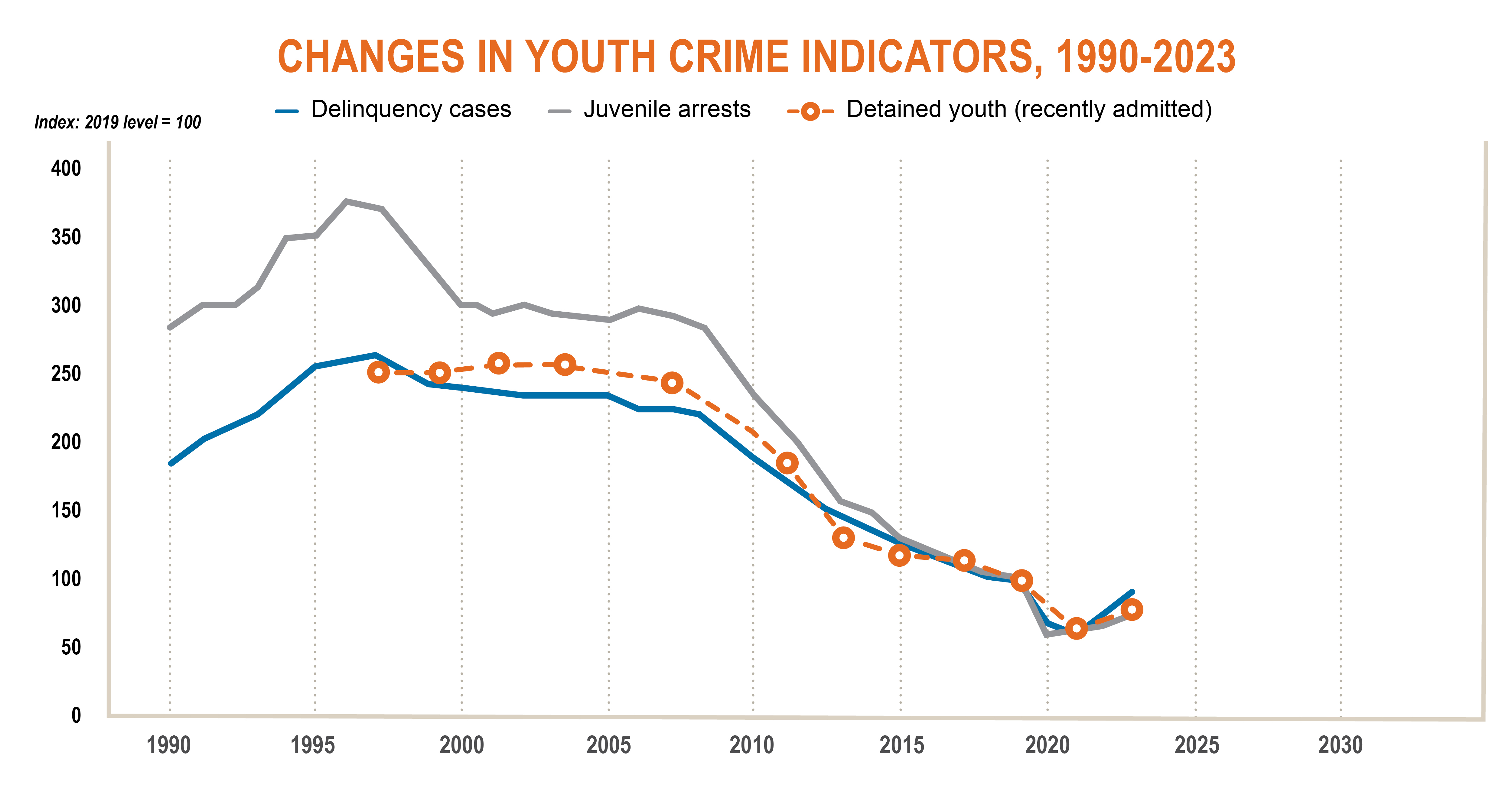

For three decades, data from these sources have told a simple, consistent story: Law-breaking by young people fell sharply. According to FBI data compiled by the Council on Criminal Justice, juvenile arrests fell 71% from 1995 to 2019. The decrease included serious violent crimes, which declined 67% — more than twice as much as adult violent arrests declined (31%) over the same period. As shown in Chart 1, the number of delinquency cases disposed in juvenile courts followed a similar pattern, peaking in the mid-1990s and declining more than 60% through 2019.

Over those same years, juvenile justice systems became less reliant on incarceration and more focused on diversion and rehabilitation. While it took several years of declining arrests before detention admissions began to fall, the two then declined in tandem for more than a decade between 2003 and 2019.

The Pandemic Disruption

With the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the juvenile justice system was jolted. Initially, arrests, delinquency cases and detention admissions fell precipitously. But no sooner did this historic decline set in, than the prevalence of some very serious crimes went up, especially those involving guns and car thefts. By 2022 and 2023, those juvenile justice indicators that had been falling for decades were rising again. For the first time since the 1990s, there appeared to be an upswing in youth crime.

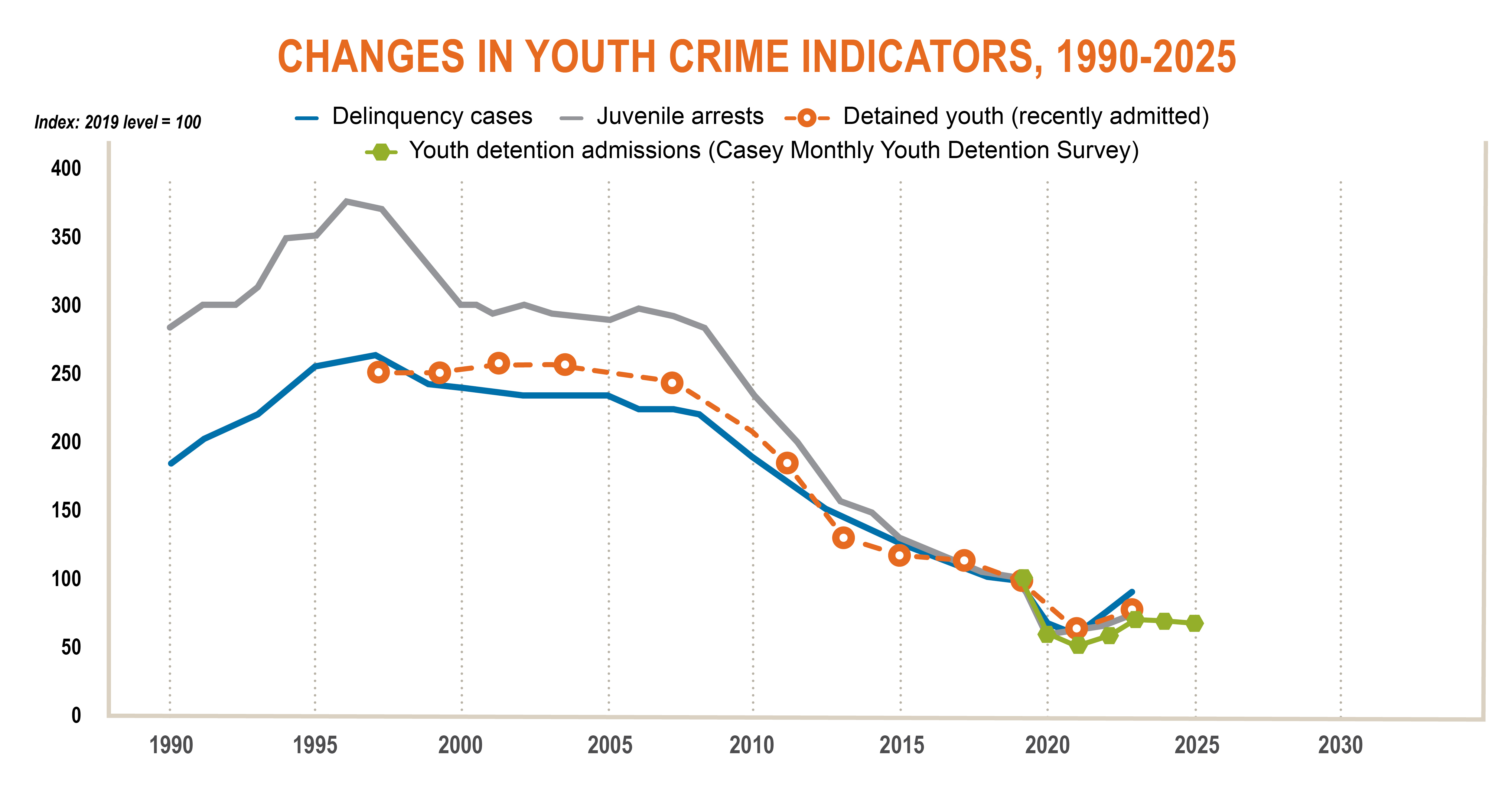

Thankfully, this has proven to be an interruption in the long-term trends — not a reversal — as shown in the analysis below.

The first important piece of evidence is the national data on juvenile arrests for 2024 that have recently become available. They show that juvenile arrests are down: 28% lower than 2019 (before COVID) and 4% lower than 2023. Notably, since 2019, arrests of young people have declined by more than arrests of adults.

What about arrests for serious violent crimes? Following an unprecedented 28% drop in 2020, juvenile arrests for these offenses did increase through 2023, essentially catching up with the rate of change in adult violent arrests. But in 2024, violent arrests went down again for both adults and juveniles and remained significantly lower than in 2019 (by 16% for adults and 12% for juveniles).

The second piece of evidence is provided by the Casey Foundation’s Monthly Youth Detention Survey. Since the start of the pandemic, the Casey Foundation has run a monthly survey of youth detention across a large swath of the country. Over the last six years, trends in the survey have aligned quite closely with other national indicators when those eventually became available. The monthly survey sites reached a post-pandemic peak for youth detention admissions in May 2023. They’ve trended downward since then and were nearly 30% below the pre-COVID level as of the end of 2025.

National data for 2025 will not be available for some time, but other leading indicators like the Real Time Crime Index are sending the same signal as the Casey survey: The decline in both violent and nonviolent crimes that began in 2023 has been accelerating since then. There is every reason to think that when national data for 2025 becomes available, it will show that youth crime continued to decline.

This is not to say that the level of youth crime today is “acceptably low.” It isn’t. It can go lower. All of us should be deeply concerned about how to lower it and work diligently to do so. Youth crime is an addressable problem, and these data make clear it is trending downward.

Over decades of reducing youth crime, the field has learned a lot about what helps young people move forward to a safe, law-abiding, productive adulthood — and what holds them back. We don’t have to throw out that playbook. Rather, we need to recommit to doing more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

Two Stubborn Truths

It’s important to acknowledge two things that have not changed over the years, despite those big swings in youth crime indicators.

First: The salience of race and ethnicity continue to be undeniably and unacceptably high. Communities of color — especially Black families — still bear the heaviest burdens of crime and system involvement. Kids of color — especially Black boys — are still more likely to face the juvenile justice system’s harshest sanctions. Those disparities have, if anything, worsened in recent years. Focusing on those disparities is essential, not just as a matter of fairness, but in terms of effectiveness. If we want safer communities and more young people reaching their potential, the data are telling us which communities we must listen to, lift up and work alongside. We don’t have to choose between being more equitable and more effective. The two go hand in hand.

Second: It remains a mistake to conflate youth crime and violent crime. Violent crimes are shocking and tragic, and the extra jolt of concern we feel when they’re committed by a young person is a justified human impulse. But the fact is that violent crime is overwhelmingly an adult problem. The most serious violent crimes account for less than 10% of all juvenile crime, and juveniles account for only about 10% of all arrests for those crimes. Focusing only on the narrow intersection between youth crime and violent crime fails to address the bulk of either problem. It’s not just unfair to blame young people for society-wide trends in violence, it’s also counterproductive.

Two Takeaways

There are two big takeaways from recent trends in youth crime.

First, from three decades of reform, we’ve seen that strategies built on the following pillars work:

- prioritizing diversion and rehabilitation;

- providing accountability in tandem with resources and opportunities;

- connecting young people with caring adults; and

- restoring ties to family and community, not severing them.

Second, the evidence tells us that less youth incarceration is still compatible with less youth crime. Incarceration isn’t a complement to the strategies that work. It’s a distraction from them at best and can actively undermine them at worst.

Call to Action

When young people harm others or break the law, accountability is essential — but it’s not the whole answer. Young people also need opportunities, support and, most importantly, caring adults to help them find a positive path forward. If you ask young people who’ve emerged and moved on from involvement in crime what helped them get back on track, they will rarely name a facility or a program. They’ll always name a person.

So let’s take the problem of youth crime seriously. Let’s not settle for forms of accountability that fail to provide the opportunity, support and connection that young people need. Let’s commit to doing what works for every child who breaks the law. Let’s make our communities safer by helping all children thrive.

Sources used for Charts 1 and 2

- Juvenile arrests: Council on Criminal Justice, Who Gets Arrested in America: Trends Across Four Decades, 1980–2024 (December 2025).

- Delinquency cases: Juvenile Court Statistics Program (JCS), delinquency cases disposed for the years 1990–2022.

- Detained Youth (recently admitted): Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (CJRP) count of youth in residential placement with detained status.

- Youth Detention Admissions: Monthly Youth Detention Survey (MYDS) sponsored by the Casey Foundation. Annual detention admissions tabulated based on monthly admissions in MYDS participating jurisdictions from January 2020 through June 2025 (annual figures estimated for 2019 based on admissions in the pre-COVID months of Jan–Mar 2020; and for 2025 based on monthly totals for Jan–jun 2025). The MYDS covers approximately 20% of the United States youth population. Trends in MYDS admissions from 2020 through 2023 have closely tracked national detention admission indicators from the JCS and CJRP.