Working With Casey, Oklahoma Doubles its Number of Licensed Foster Care Beds

The Annie E. Casey Foundation teamed up with the state of Oklahoma to improve its foster care system, and the multiyear collaboration is yielding impressive results.

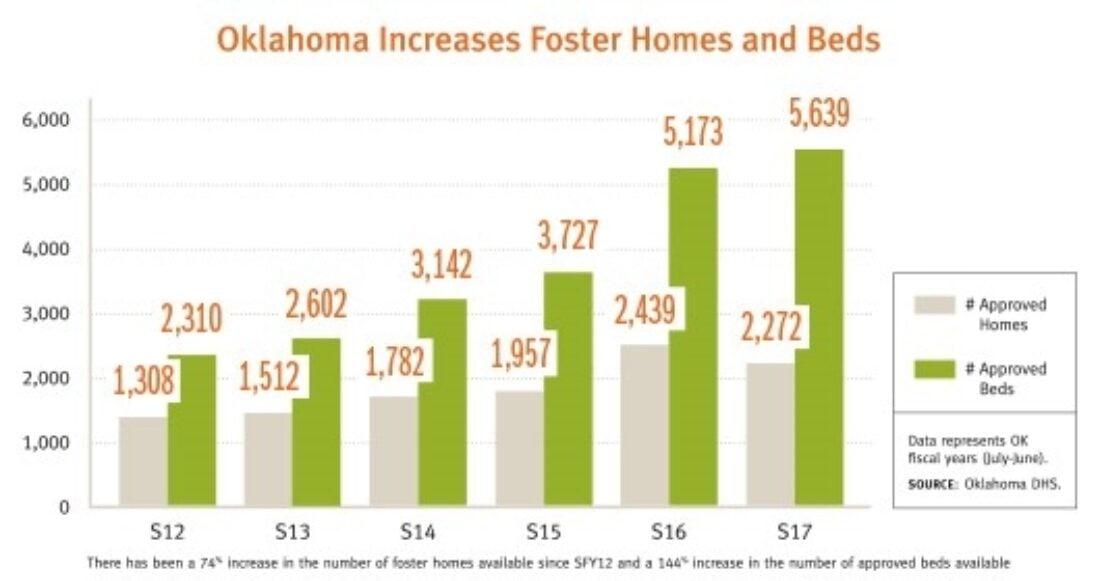

Oklahoma’s child welfare system — ranked among the nation’s poorest performing systems not long ago — has shown the greatest increase in foster home capacity nationwide, according to a recent report. In just three years, the state’s Department of Human Services (DHS) has doubled the number of approved foster beds, reaching almost 5,500 by the end of 2017.

This increased capacity occurred at a time when the number of children and youth in foster care declined statewide.

Casey’s engagement with DHS had two aims:

- retain, recruit and effectively support foster parents, with the goal of ending the practice of placing children in group facilities; and

- guide the department’s implementation of child safety meetings, a team decision making model that emphasizes engaging families and communities in child safety, removal and placement decisions.

The Foundation’s Child Welfare Strategy Group (CWSG) partnered with DHS staff to design and implement a robust foster parent recruitment campaign. The group also worked to shift DHS away from using short-term shelters for children — an effort mandated by a 2012 settlement of a federal class-action lawsuit that significantly increased the demand for foster and kinship care.

“Oklahoma’s child welfare professionals focused on ensuring more children are placed with families, where our research and experience tells us they do best,” says Tracey Feild, CWSG’s director. “They also understand that it isn’t enough to simply sign up more foster parents. They are prioritizing making foster parents full partners in raising the children in their care, and they are offering support every step of the way.”

The collaboration’s approach was comprehensive, with an eye toward long-term sustainability. DHS enhanced how it worked with both private agencies and tribal organizations. The department also adapted the Foundation’s Foster Home Estimator, a data-analysis tool that enables users to identify geographic areas where foster parents are needed most. The tool helped DHS pinpoint specific family types — such as those able to accommodate older children and sibling groups — that were in high demand.

“Child welfare systems are always chasing after the next shiny thing, often without considering what they want their practices and outcomes to look like five or 10 years down the line,” says Jami Ledoux, DHS director of child welfare services. “This partnership allowed us to engage in thoughtful planning and preparation for sustainable improvements.”

In addition to introducing new training protocols, Casey worked with DHS staff to implement child safety meetings (CSMs). This practice — which involves families, caregivers and professionals — can help prevent children from being unnecessarily removed from their homes.

“CSMs have impacted how we think about our role in people’s lives and our work across the board,” Ledoux says. “The decisions we reach through that process literally determine where a child sleeps at night.”

Tricia Howell, DHS deputy director of foster care and adoption, credits Casey with challenging the department to make significant service improvements while also supplying the needed research and frontline support. “Every state in the nation is suffering right now,” Howell says. “Through the breadth of knowledge and the level of experience the Casey team brought to the table, we learned what works, what is possible and what we can do within our resources to protect and care for Oklahoma’s children.”

Child welfare agencies in other states can learn from Oklahoma’s successes. Some lessons worth repeating:

- Effective systems change often involves encouraging the larger community, including advocates, to support the child welfare agency’s reform agenda.

- Agencies must find ways to ensure that leaders from both public and private providers are part of the solution. Feild points to recent comments in Tulsa World by Keith Howard, a vice president for the Oklahoma United Methodist Circle of Care, a foster care services provider. The individuals driving improvements in Oklahoma, says Howard, “spanned the spectrum, from state officials… to private agency leadership… There was a common theme among these leaders, ‘Let’s be committed to making Oklahoma better through increasing foster homes and finding ways to keep kids out of foster care.’”

- In states with significant indigenous populations, tribal organizations can be key partners. Oklahoma DHS worked intensively with tribal organizations, which helped to build relationships and boost the number of tribal foster families.